Difference between revisions of "Transposition"

m (→Optimization possibilities for transposition) |

m (→Transposition, repeated inheritance and replication) |

||

| (94 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | With the ECMA Eiffel Standard, the dynamic binding semantics of the Eiffel language are | + | [[Category:ECMA]] |

| − | + | Author: Matthias Konrad | |

| − | + | ==Description== | |

| − | + | ====The new dynamic binding semantics==== | |

| − | + | With the ECMA Eiffel Standard, the dynamic binding semantics of the Eiffel language are almost clearly defined. This new or clarified semantics have some interesting consequences. The following system shows the difference between how the dynamic semantics were (and still are) implemented and how they are specified in the ECMA standard: | |

| − | + | ||

{|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | {|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | ||

|-valign="top" -halign="center" | |-valign="top" -halign="center" | ||

| − | |<code>[eiffel, N] | + | |[[Image:SC_ABC.jpg|280px]] |

| − | + | | | |

| − | B | + | <code>[eiffel,N] |

| − | + | local | |

| − | f | + | a: A |

| − | + | b: B | |

| + | do | ||

| + | create {C}a | ||

| + | create {C}b | ||

| + | a.f --Line 3 | ||

| + | b.f1 --Line 4 | ||

end | end | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The semantics for line 3 have always been clear, feature ''f2'' should be called. For line 4 the ECMA standard says, that feature ''f1'' is called, whereas the current ISE compiler chooses feature ''f2''. So the ECMA standard restrains the power of select; it only has an impact if there are two or more inheritance paths from the static type to the dynamic type. This is indeed the case for line 3 but not for line 4 of the above example. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The lesson learned is: | ||

| + | *The exact static type of an entity has an important influence on the dynamic binding. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Covariance and the missing part of the ECMA standard==== | ||

| + | Eiffel allows covariant redefinitions. We reuse the previous example system and add two new classes ''X'' and ''Y'': | ||

| + | |||

| + | {|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | ||

| + | |-valign="top" -halign="center" | ||

| + | |[[Image:Example.jpg|450px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Class ''Y'' covariantly redefines feature ''a'' to the more specific type ''B''. We are interested in the semantics of feature ''g'' when executed on an object of class ''Y''. For this we need to know whether the static type of field ''a'' is ''A'' or ''B''. Of course the static type from the perspective of feature ''g'' is still ''A'', ''f'' is not even a valid feature name on a target of type ''B''. But the flat-short representation of ''Y'' tells us something different (Features of ''ANY'' omitted): | ||

| + | |||

| + | {|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | ||

| + | |-valign="top" -halign="center" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <code>[eiffel, N] | + | <code>[eiffel,N] |

| − | class | + | class |

| − | + | Y | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

feature | feature | ||

| − | + | a: B | |

| + | g | ||

| + | do | ||

| + | a.f1 | ||

| + | end | ||

end | end | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | class | + | So according to the flat-short representation, when ''g'' is executed on an object of class ''Y'', the static type of ''a'' is ''B''. The flat-short thus implies an other dynamic-binding semantics than the one currently described in ECMA. |

| + | |||

| + | ====Transposition==== | ||

| + | In the flat-short representation all the inherited features are transposed to the class. It is this transposition that causes the problem. Transposition is also used for the new join semantics (ECMA-3). Furthermore it should be used in the definition of some unfolded forms (for example for the unfolded form of an assertion (8.10.2) or replication). We may say, that if the transposition of a specimen is semantically contradicting then this is a huge problem not only but also because the ECMA standard heavily relies on unfolded forms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Or we state, that the unfolded form of a class has all its inherited features transposed. The unfolded form of class ''Y'' would be: (we again omit the ''ANY'' stuff) | ||

{|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | {|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | ||

| − | |-valign="top" -halign="center"| | + | |-valign="top" -halign="center" |

| − | <code>[eiffel, N] | + | | |

| + | <code>[eiffel,N] | ||

class | class | ||

| − | + | Y | |

inherit | inherit | ||

| − | + | X redefine a, b end | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

feature | feature | ||

| − | + | a: B | |

| − | + | g | |

| − | + | do | |

| − | + | a.f1 | |

| + | end | ||

end | end | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Apart from the inheritance clause, this unfolded form is similar to the flat-short view of the class. In this unfolded form the inheritance relationship is degraded to a pure subtyping, no feature of ''X'' is ever executed for an object of type ''Y''. This is very convenient, for every class we get both its definitive features and its subtype relation. One interesting property of this is, that every unqualified call is statically bound. | |

| − | + | Conclusions: | |

| − | + | *With the old dynamic-binding semantics it does not matter whether or not something is transposed. | |

| + | *With the new semantics we need to either transpose always or never. Since transposition is indeed needed every inherited feature needs to be transposed. | ||

| − | + | ====Incremental transposition==== | |

| + | To construct the transposed form of a class, the transposed forms of its direct base classes are needed. To illustrate that we show class ''Z'' and its transposition: | ||

| − | + | {|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | |

| − | + | |-valign="top" -halign="center" | |

| − | <code>[ | + | | |

| − | + | <code>[eiffel,N] | |

| − | + | class | |

| − | + | Z | |

| − | end | + | inherit |

| + | Y redefine a end | ||

| + | feature | ||

| + | a: C | ||

| + | end | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | <code>[eiffel,N] | |

| − | + | class | |

| − | + | Z | |

| − | + | inherit | |

| − | + | Y redefine a,g end | |

| − | + | feature | |

| − | + | a: C | |

| − | + | g | |

| − | + | do | |

| − | + | a.f1 | |

| − | + | end | |

| − | + | end | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <code>[ | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | do | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | Would we have constructed the unfolded form of ''Z'' based on ''X'', then feature ''g'' would call feature ''f2''. | ||

| + | ====Transposition, repeated inheritance and replication==== | ||

| + | We show now, that transposition simplifies the discussion of repeated inheritance and replication. Lets forget for a moment everything we know about replication (ECMA rules 8.16.2, 8.16.3, 8.16.4, 8.16.5), we only need to specify what happens if two transposed features happen to have the same name as in the following two systems ''S1'' and ''S2'': | ||

| + | {|border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" align="center" | ||

| + | |-valign="top" -halign="center" | ||

| + | |[[Image:TransRep.jpg]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The unfolded form of class ''B'' has two features with name ''f'', since both of them are the same they can just be joined. The unfolded form of class ''D'' also has two features with name ''g''. One of this features calls ''f1'' and the other one calls ''f2''. This is clearly a conflict. Two transposed features should be allowed to have the same name if and only if they are identical. | ||

| + | This is all there is to say about replication. Again, the fact, that we have a definite set of features for every class makes things simpler. | ||

| + | ====Optimization possibilities for transposition==== | ||

| + | Apart from its power to describe the semantics of the language, transposition is very (maybe too) expensive. It is certainly not acceptable to really transpose every feature. So we need to find criteria to only transpose when really needed. Interestingly this is quite difficult but it is maybe better to have a simple language and complex compilers than the opposite. | ||

| + | ==Summary== | ||

| + | * Transposition clarifies semantics of feature calls in the ECMA standard. | ||

| + | * The new dynamic binding semantics forces every class to perform a transposition of all its inherited features (with little space for optimization, see [[Transposition#Optimization_possibilities_for_transposition|above]]) | ||

| − | + | Given the above, one could ask whether the new dynamic binding rules make sense: | |

| − | + | # If we use the semantics of the Eiffel Software compiler, transposition only needs to be done for replicated features, thus simplifying the work for compiler writers. | |

| − | + | # The semantics get clearer since by just looking at the text of a class you know which feature will be called (no need for you to perform a mental incremental transposition). | |

| + | # In real life, there are few occurrences of repeated inheritance that need a select. | ||

Latest revision as of 14:57, 13 November 2006

Author: Matthias Konrad

Contents

Description

The new dynamic binding semantics

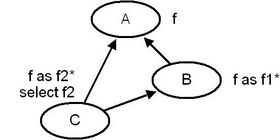

With the ECMA Eiffel Standard, the dynamic binding semantics of the Eiffel language are almost clearly defined. This new or clarified semantics have some interesting consequences. The following system shows the difference between how the dynamic semantics were (and still are) implemented and how they are specified in the ECMA standard:

|

local a: A b: B do create {C}a create {C}b a.f --Line 3 b.f1 --Line 4 end |

The semantics for line 3 have always been clear, feature f2 should be called. For line 4 the ECMA standard says, that feature f1 is called, whereas the current ISE compiler chooses feature f2. So the ECMA standard restrains the power of select; it only has an impact if there are two or more inheritance paths from the static type to the dynamic type. This is indeed the case for line 3 but not for line 4 of the above example.

The lesson learned is:

- The exact static type of an entity has an important influence on the dynamic binding.

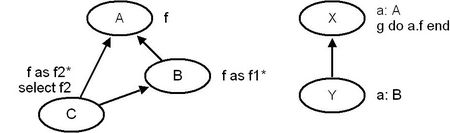

Covariance and the missing part of the ECMA standard

Eiffel allows covariant redefinitions. We reuse the previous example system and add two new classes X and Y:

|

Class Y covariantly redefines feature a to the more specific type B. We are interested in the semantics of feature g when executed on an object of class Y. For this we need to know whether the static type of field a is A or B. Of course the static type from the perspective of feature g is still A, f is not even a valid feature name on a target of type B. But the flat-short representation of Y tells us something different (Features of ANY omitted):

class Y feature a: B g do a.f1 end end |

So according to the flat-short representation, when g is executed on an object of class Y, the static type of a is B. The flat-short thus implies an other dynamic-binding semantics than the one currently described in ECMA.

Transposition

In the flat-short representation all the inherited features are transposed to the class. It is this transposition that causes the problem. Transposition is also used for the new join semantics (ECMA-3). Furthermore it should be used in the definition of some unfolded forms (for example for the unfolded form of an assertion (8.10.2) or replication). We may say, that if the transposition of a specimen is semantically contradicting then this is a huge problem not only but also because the ECMA standard heavily relies on unfolded forms.

Or we state, that the unfolded form of a class has all its inherited features transposed. The unfolded form of class Y would be: (we again omit the ANY stuff)

class Y inherit X redefine a, b end feature a: B g do a.f1 end end |

Apart from the inheritance clause, this unfolded form is similar to the flat-short view of the class. In this unfolded form the inheritance relationship is degraded to a pure subtyping, no feature of X is ever executed for an object of type Y. This is very convenient, for every class we get both its definitive features and its subtype relation. One interesting property of this is, that every unqualified call is statically bound.

Conclusions:

- With the old dynamic-binding semantics it does not matter whether or not something is transposed.

- With the new semantics we need to either transpose always or never. Since transposition is indeed needed every inherited feature needs to be transposed.

Incremental transposition

To construct the transposed form of a class, the transposed forms of its direct base classes are needed. To illustrate that we show class Z and its transposition:

class Z inherit Y redefine a end feature a: C end |

class Z inherit Y redefine a,g end feature a: C g do a.f1 end end |

Would we have constructed the unfolded form of Z based on X, then feature g would call feature f2.

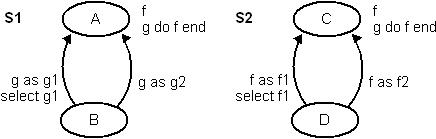

Transposition, repeated inheritance and replication

We show now, that transposition simplifies the discussion of repeated inheritance and replication. Lets forget for a moment everything we know about replication (ECMA rules 8.16.2, 8.16.3, 8.16.4, 8.16.5), we only need to specify what happens if two transposed features happen to have the same name as in the following two systems S1 and S2:

|

The unfolded form of class B has two features with name f, since both of them are the same they can just be joined. The unfolded form of class D also has two features with name g. One of this features calls f1 and the other one calls f2. This is clearly a conflict. Two transposed features should be allowed to have the same name if and only if they are identical. This is all there is to say about replication. Again, the fact, that we have a definite set of features for every class makes things simpler.

Optimization possibilities for transposition

Apart from its power to describe the semantics of the language, transposition is very (maybe too) expensive. It is certainly not acceptable to really transpose every feature. So we need to find criteria to only transpose when really needed. Interestingly this is quite difficult but it is maybe better to have a simple language and complex compilers than the opposite.

Summary

- Transposition clarifies semantics of feature calls in the ECMA standard.

- The new dynamic binding semantics forces every class to perform a transposition of all its inherited features (with little space for optimization, see above)

Given the above, one could ask whether the new dynamic binding rules make sense:

- If we use the semantics of the Eiffel Software compiler, transposition only needs to be done for replicated features, thus simplifying the work for compiler writers.

- The semantics get clearer since by just looking at the text of a class you know which feature will be called (no need for you to perform a mental incremental transposition).

- In real life, there are few occurrences of repeated inheritance that need a select.