Difference between revisions of "Internationalization/Developer guide"

(added translation section) |

m |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Category:Internationalization]] | ||

=General architecture of the i18n library= | =General architecture of the i18n library= | ||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

#A part which provides an interface to the information | #A part which provides an interface to the information | ||

| − | [[Image:i18n_overview.png|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:i18n_overview.png|thumb|right|500px|General structure of the i18n library]] |

| − | An overview of the structure is provided to the right: the two central classes, LOCALE and LOCALE_MANAGER are the main interface classes. The rightmost | + | An overview of the structure is provided to the right: the two central classes, LOCALE and LOCALE_MANAGER are the main interface classes. The rightmost class, HOST_LOCALE, is responsible for fetching the formatting information, and the leftmost class, DATASOURCE_MANAGER, must deal with finding the translation of strings. |

In addition there are several classes that are used to encapsulate information, not shown on diagrams to avoid them resembling a web drawn by an overcaffeinated spider. | In addition there are several classes that are used to encapsulate information, not shown on diagrams to avoid them resembling a web drawn by an overcaffeinated spider. | ||

| Line 26: | Line 27: | ||

Obviously it should not be the user's job to do all this initialisation. This is why there must be a class that is in charge of presenting the user with a choice of locales and giving the user a correctly initialised LOCALE for the locale ultimately chosen. | Obviously it should not be the user's job to do all this initialisation. This is why there must be a class that is in charge of presenting the user with a choice of locales and giving the user a correctly initialised LOCALE for the locale ultimately chosen. | ||

| − | This class is LOCALE_MANAGER. A LOCALE_MANAGER uses | + | This class is LOCALE_MANAGER. A LOCALE_MANAGER uses an implementation of HOST_LOCALE and a DATASOURCE_MANAGER to find out for which locales formatting information and/or translations are available and can provide the client with a list of supported locales. |

A locale is identified by a LOCALE_ID object; this is not only used internally but also by the client when requesting a LOCALE object. | A locale is identified by a LOCALE_ID object; this is not only used internally but also by the client when requesting a LOCALE object. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Formatting information== | ==Formatting information== | ||

| − | [[Image:i18n_locale_information.png|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:i18n_locale_information.png|thumb|right|500px|Section of the i18n library that retrieves locale information]] |

Most major operating systems have an API that provides localisation information. Often they also allow clients to format dates, times and values directly. We decided that instead of directly using the formatting functions of the operating system, we would write our own formatters in Eiffel. Retrieving the required information, however, still has to be done in C. Depending on the operating system, this is a more-or-less simple process. | Most major operating systems have an API that provides localisation information. Often they also allow clients to format dates, times and values directly. We decided that instead of directly using the formatting functions of the operating system, we would write our own formatters in Eiffel. Retrieving the required information, however, still has to be done in C. Depending on the operating system, this is a more-or-less simple process. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 38: | ||

The formatting information for a given locale is stored in objects of class LOCALE_INFO. Each LOCALE_INFO is initialized on creation with (what we think are sensible) default values, as not all platforms provide all the same information. | The formatting information for a given locale is stored in objects of class LOCALE_INFO. Each LOCALE_INFO is initialized on creation with (what we think are sensible) default values, as not all platforms provide all the same information. | ||

| − | LOCALE_MANAGER is able to retrieve the LOCALE_ID of the default locale, filled LOCALE_INFOS and a list of locales with formatting information from a | + | LOCALE_MANAGER is able to retrieve the LOCALE_ID of the default locale, filled LOCALE_INFOS and a list of locales with formatting information from a HOST_LOCALE_IMP. |

| − | + | ||

The deferred class HOST_LOCALE* specifies the interface for operating system-specific implementations, and the right effective class, HOST_LOCALE_IMP, is included in the system through a conditional statement in the .ecf platform. This class normally makes use of C externals to actually access the formatting information, although the .NET implementation is an exception. The main jobs that it has are: assembling a list of supported locales, creating, filling and returning a LOCALE_INFO for a given locale, and identifying the locale set as default in the operating system preferences. | The deferred class HOST_LOCALE* specifies the interface for operating system-specific implementations, and the right effective class, HOST_LOCALE_IMP, is included in the system through a conditional statement in the .ecf platform. This class normally makes use of C externals to actually access the formatting information, although the .NET implementation is an exception. The main jobs that it has are: assembling a list of supported locales, creating, filling and returning a LOCALE_INFO for a given locale, and identifying the locale set as default in the operating system preferences. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 48: | ||

| − | [[Image:i18n_translation.png|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:i18n_translation.png|thumb|right|500px|Section of the i18n library that retrieves translations]] |

The part of the library that provides translated strings is slightly more complicated. The strings come from a so-called data source (or datasource, depending on preference). The uri given to a LOCALE_MANAGER on creation is examined by a URI_PARSER, which decides what sort of data source this uri represents. It then creates an appropriate DATASOURCE_MANAGER* with this uri and returns it to the LOCALE_MANAGER. | The part of the library that provides translated strings is slightly more complicated. The strings come from a so-called data source (or datasource, depending on preference). The uri given to a LOCALE_MANAGER on creation is examined by a URI_PARSER, which decides what sort of data source this uri represents. It then creates an appropriate DATASOURCE_MANAGER* with this uri and returns it to the LOCALE_MANAGER. | ||

| − | From this point onwards the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* is responsible for the main operations involving translations: providing a list of locales for which a translation is present, and providing the translation in form of a DICTIONARY* for a given locale. | + | From this point onwards the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* is responsible for the main operations involving translations: providing a list of locales and languages for which a translation is present, and providing the translation in form of a DICTIONARY* for a given locale. |

A DICTIONARY* is nothing more then a collection of translated strings, with functions to access them. There are several effective descendants, as the best way to store the strings may depend on several factors (singular/plural ration, data source itself, etc.). The LOCALE_MANAGER gets the relevant DICTIONARY* from the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* and passes it to the LOCALE on creation. The LOCALE can then retrieve translations. | A DICTIONARY* is nothing more then a collection of translated strings, with functions to access them. There are several effective descendants, as the best way to store the strings may depend on several factors (singular/plural ration, data source itself, etc.). The LOCALE_MANAGER gets the relevant DICTIONARY* from the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* and passes it to the LOCALE on creation. The LOCALE can then retrieve translations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If there are translations for both a locale itself and it's language, the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* will of course return a DICTIONARY* containing the translations specifically for that locale. If there is no translation for the locale but one exists for it's language, that will be used. | ||

===File data source === | ===File data source === | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

The file datasource works in the following way: | The file datasource works in the following way: | ||

The FILE_MANAGER, an effective DATASOURCE_MANAGER*, has a chain-of-responsibility built from FILE_HANDLER*s. | The FILE_MANAGER, an effective DATASOURCE_MANAGER*, has a chain-of-responsibility built from FILE_HANDLER*s. | ||

| − | There are two operations provided by this chain of responsibility: determining the | + | There are two operations provided by this chain of responsibility: determining the scope of a file (i.e which language or locale it corresponds to) and providing a DICTIONARY* containing the strings from this file. |

| − | By using this chain and a list of | + | By using this chain and a list of files in the current directory, the FILE_MANAGER can list available locales, list available languages and provide DICTIONARY* objects. The precise type of DICTIONARY* provided is dependant on the type of file. |

Each FILE_HANDLER* works by using a FILE* object, which provides the actual parsing functionality for a given file type. | Each FILE_HANDLER* works by using a FILE* object, which provides the actual parsing functionality for a given file type. | ||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

===FILE_MANAGER=== | ===FILE_MANAGER=== | ||

| − | Currently FILE_MANAGER has the simplistic policy of only examining files in the current directory and trusting their name. It is very well possible that there is a project policy of placing each locale in it's own directory (KDE does this) | + | Currently FILE_MANAGER has the simplistic policy of only examining files in the current directory and trusting their name. It is very well possible that there is a project policy of placing each locale in it's own directory (KDE does this) or of having a translation spanned over multiple .mo files for one locale. |

A good place to implement such a project-dependant policy is a descendant of FILE_MANAGER, or an entirely new data source. | A good place to implement such a project-dependant policy is a descendant of FILE_MANAGER, or an entirely new data source. | ||

Latest revision as of 07:45, 31 October 2006

Contents

General architecture of the i18n library

Where does the information come from?

The i18n library must obviously knows how to format things and finds translations for many different locales. Translations are application-dependant and thus we only have to deal with them on an infrastructural basis - the actual information is supplied by the user. However formatting information is not. Instead, we can fetch this from the operating system.

This leads us to divide the library into three main parts:

- A part which organises and provides translations from a user-supplied data source.

- A part which retrieves formatting information from the host operating system

- A part which provides an interface to the information

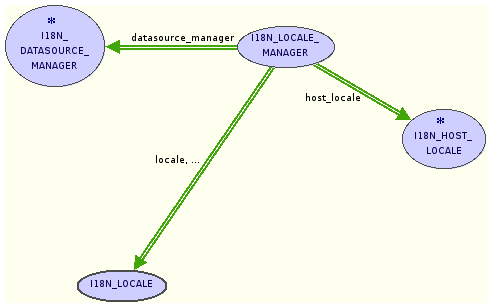

An overview of the structure is provided to the right: the two central classes, LOCALE and LOCALE_MANAGER are the main interface classes. The rightmost class, HOST_LOCALE, is responsible for fetching the formatting information, and the leftmost class, DATASOURCE_MANAGER, must deal with finding the translation of strings.

In addition there are several classes that are used to encapsulate information, not shown on diagrams to avoid them resembling a web drawn by an overcaffeinated spider.

Note: the 'I18N' prefix of class names is omitted in the text for clarity.

Interface

The main two classes of the interface are, as has been previously stated, LOCALE and LOCALE_MANAGER. LOCALE represents all operations associated with a given locale: formatting and translation. This is the class that clients use to actually localise things, but all it does is provide wrapper functions: the translations are retrieved from a DICTIONARY (more on this later) provided to it on creation, and the formatting is done by specialised formatting classes (DATE_FORMATTER, VALUE_FORMATTER, STRING_FORMATTER and CURRENCY_FORMATTER) which are also operated with information passed in a LOCALE_INFO object to the LOCALE on creation.

Obviously it should not be the user's job to do all this initialisation. This is why there must be a class that is in charge of presenting the user with a choice of locales and giving the user a correctly initialised LOCALE for the locale ultimately chosen. This class is LOCALE_MANAGER. A LOCALE_MANAGER uses an implementation of HOST_LOCALE and a DATASOURCE_MANAGER to find out for which locales formatting information and/or translations are available and can provide the client with a list of supported locales. A locale is identified by a LOCALE_ID object; this is not only used internally but also by the client when requesting a LOCALE object.

Formatting information

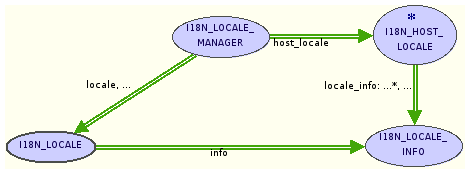

Most major operating systems have an API that provides localisation information. Often they also allow clients to format dates, times and values directly. We decided that instead of directly using the formatting functions of the operating system, we would write our own formatters in Eiffel. Retrieving the required information, however, still has to be done in C. Depending on the operating system, this is a more-or-less simple process.

The formatting information for a given locale is stored in objects of class LOCALE_INFO. Each LOCALE_INFO is initialized on creation with (what we think are sensible) default values, as not all platforms provide all the same information.

LOCALE_MANAGER is able to retrieve the LOCALE_ID of the default locale, filled LOCALE_INFOS and a list of locales with formatting information from a HOST_LOCALE_IMP.

The deferred class HOST_LOCALE* specifies the interface for operating system-specific implementations, and the right effective class, HOST_LOCALE_IMP, is included in the system through a conditional statement in the .ecf platform. This class normally makes use of C externals to actually access the formatting information, although the .NET implementation is an exception. The main jobs that it has are: assembling a list of supported locales, creating, filling and returning a LOCALE_INFO for a given locale, and identifying the locale set as default in the operating system preferences. Currently there are HOST_LOCALE_IMP classes for .NET, Windows, and what should be more or less POSIX - only, for now, tested under linux.

Translations

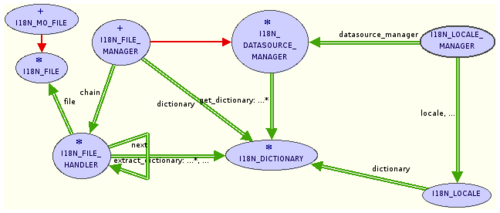

The part of the library that provides translated strings is slightly more complicated. The strings come from a so-called data source (or datasource, depending on preference). The uri given to a LOCALE_MANAGER on creation is examined by a URI_PARSER, which decides what sort of data source this uri represents. It then creates an appropriate DATASOURCE_MANAGER* with this uri and returns it to the LOCALE_MANAGER.

From this point onwards the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* is responsible for the main operations involving translations: providing a list of locales and languages for which a translation is present, and providing the translation in form of a DICTIONARY* for a given locale. A DICTIONARY* is nothing more then a collection of translated strings, with functions to access them. There are several effective descendants, as the best way to store the strings may depend on several factors (singular/plural ration, data source itself, etc.). The LOCALE_MANAGER gets the relevant DICTIONARY* from the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* and passes it to the LOCALE on creation. The LOCALE can then retrieve translations.

If there are translations for both a locale itself and it's language, the DATASOURCE_MANAGER* will of course return a DICTIONARY* containing the translations specifically for that locale. If there is no translation for the locale but one exists for it's language, that will be used.

File data source

The file datasource works in the following way: The FILE_MANAGER, an effective DATASOURCE_MANAGER*, has a chain-of-responsibility built from FILE_HANDLER*s. There are two operations provided by this chain of responsibility: determining the scope of a file (i.e which language or locale it corresponds to) and providing a DICTIONARY* containing the strings from this file. By using this chain and a list of files in the current directory, the FILE_MANAGER can list available locales, list available languages and provide DICTIONARY* objects. The precise type of DICTIONARY* provided is dependant on the type of file.

Each FILE_HANDLER* works by using a FILE* object, which provides the actual parsing functionality for a given file type. Currently the only supported file type is the .mo file format, so this is the only example I may provide.

Possible expansion points

We hope our library is reasonably extensible. In particular, we foresee the following areas of expansion:

New file formats

Currently we only support the .po/.mo file format. This is because we have limited time and resources and we also feel that the .mo file format is the best current choice, as it it provides plural form handling. However, there are other file formats. Trolltech has their own format, there is a Solaris message catalog format, presumably some Windows formats, and OS X also has a native format.

In order to add support for one of these formats - or your own! - it's necessary to write both FILE* and FILE_HANDLER* implementations. Then the new effective descendant of FILE_HANDLER* must be added to the chain-of-responsibility (called chain) in the make feature of FILE_MANAGER.

Data sources

New data sources

Currently we only have one implementation of DATASOURCE_MANAGER*. But maybe a file is not suited to everything. A possible data source, however far-fetched, might be a database: all strings could be fetched via queries. Or maybe all strings could be fetched via SOAP or RPC from a remote machine, to ensure up-to-date translations. More realistically one could certainly imagine a data source that checks the locally-stored translations and fetches the latest version remotely if there has been changes. The easiest way to do such things is of course to write a new effective descendant of DATASTRUCTURE*. This may or may not require a new implementation of DICTIONARY* - for a system that fetches strings on.demand rather then loading them all at initialisation, a new DICTIONARY* would certainly be advisable!

To make the library know about a new DATASOURCE_MANAGER*, URI_PARSER must be told how to recognise an uri that requires it. It is advisable to choose a nice prefix.

FILE_MANAGER

Currently FILE_MANAGER has the simplistic policy of only examining files in the current directory and trusting their name. It is very well possible that there is a project policy of placing each locale in it's own directory (KDE does this) or of having a translation spanned over multiple .mo files for one locale.

A good place to implement such a project-dependant policy is a descendant of FILE_MANAGER, or an entirely new data source.

New dictionaries

New dictionaries might be required by new data sources. Or maybe the translations used by your project can be stored in a more efficient way then the general case - one could imagine a dictionary that takes advantage of singular/plural distribution, or that is keyed to the way translations are stored in a particular file format. To add a new dictionary, it's sufficient to write an implementation of DICTIONARY* and to make sure it's used.